In this month’s edition of A Way With Words – an ongoing series of interviews with contemporary female writers – CF speaks to Tsitsi Dangaremba.

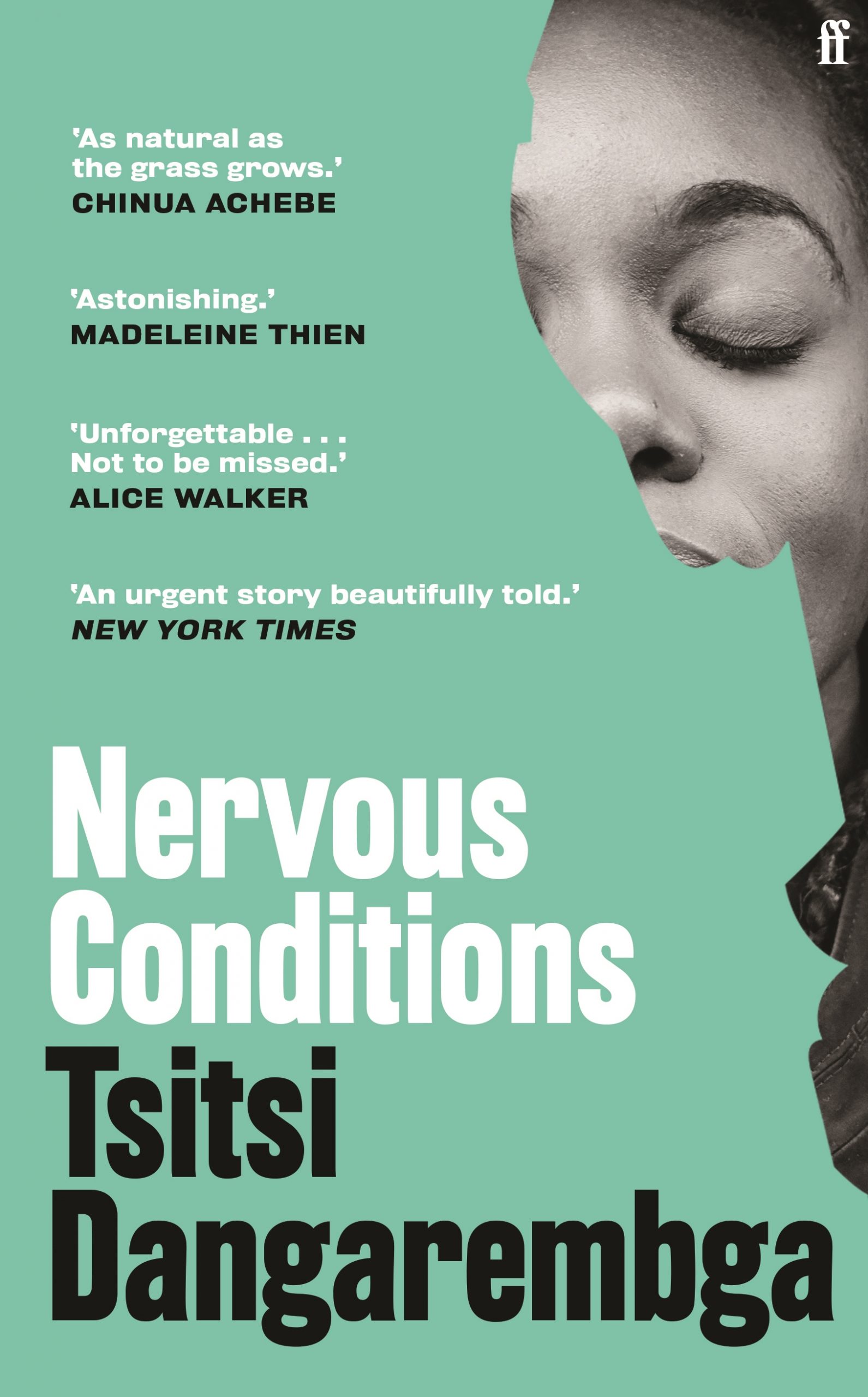

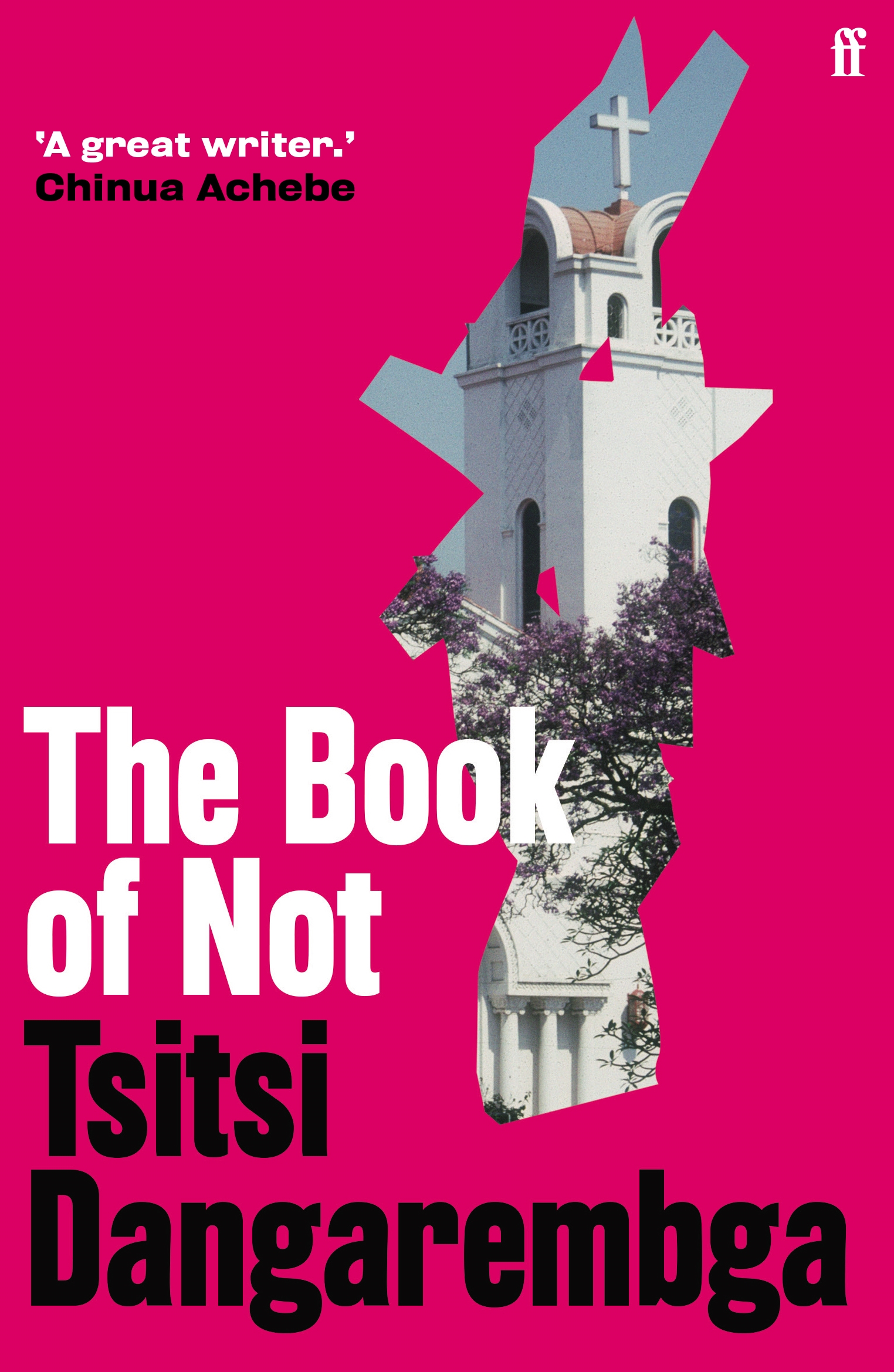

Tsitsi Dangaremba is the author of three novels, including Nervous Conditions, which was named by the BBC in 2018 as ‘one of the top 100 books that have shaped the world’, and This Mournable Body, which was long-listed for the 2020 Booker Prize. Here, she discusses the struggles of writing, her relationship with Zimbabwe, and filmmaking

What is writing for you?

So far, writing for me has been witnessing. Witnessing comes after the event, when the trauma is over. At the time that Zimbabwean society passed through the times described in the three novels of the Tambudzai Trilogy (Nervous Conditions, The Book of Not, This Mournable Body), most Zimbabweans did not realise we were living through trauma of quite a relentless variety. There was the trauma of colonialism, the trauma of patriarchy, the trauma of the war for independence, the trauma of betrayal by those who said they were our liberators, and the trauma of descent into the misery and tyranny we find ourselves in today, to say nothing of day-to-day living. These situations were made bearable by intimate moments, small successes here and there, and relationships, which I also narrate. I believe a novel needs a location of love and hope. Yet, all these traumas had real consequences felt on the bodies and in the hearts, minds and spirits of individual Zimbabwean people. Giving utterance to it was important to me, as was always pointing to a way forward no matter how bleak the world I depicted appeared. So, in effect, writing is a way of claiming a kind of happy ending from trauma, to say we are here, this is what we went through and we are engaging with it and willing better into being.

How did Nervous Conditions start? Did you always know it was going to be part of a trilogy?

I wrote NC to see women like myself in literature. There were hardly any at the time. Certainly, there were no Zimbabwean women I could relate to in literature. This meant everything that I took into myself from literature and narrative as I grew up was a representation made by, and usually about, somebody who was not at all like me. Having my mind filled with what was not me wasn’t the healthiest situation, especially as I read a lot. Women of colour in literature became available to me in the African American literature when I was a young woman. At Zimbabwe’s independence from Great Britain and the form of apartheid we had in Rhodesia, which happened in 1980, I had a sense of things opening up for people like me in my country. I felt the urge to fill the gap that existed with respect to young black African women in literature. I wanted the story I wrote to be one many people could relate to. At the time Zimbabwe’s population was over nearly 80 per cent rural, so I told the story of a young rural girl fighting to be the best versions of herself she could imagine with the tools available to her in an environment that did not give anything to her in her own right. The tool was education. The story of Nervous Conditions became the story of Tambudai Siguake fighting to go to school.

The previous two books were critically acclaimed but This Mournable Body is the one that drew widespread international attention to your work. Why do you think that is?

There were few black, African women writing when I started writing in the 1980s. Those who were writing were mainly from West Africa and quite a bit older than I was when I started writing seriously, which I did in my early twenties. My subject matter was also quite different. I wrote about young black African girls wanting to be, having ambition, and thinking they could amount to something. That was a very unusual narrative at the time. How many people in the international publishing world had seen a young African girl like that at the time? There was simply not much space in the publishing world for the people and the kind of narrative I proposed. I am so grateful to see how much this has changed in the intervening decades.

Was one easier or more difficult to write than the others?

All the books were very difficult to write. I start off with an emotion. It’s usually quite undefined. I go through a process of creating characters and situations that match the emotion, then I put it down on paper. There’s always the initial relief when I do think up a character or a situation or a setting, but then when I read what I’ve written, I realise I mistook the relief at having imagined something was the match I wanted with the original emotional impulse. It reads all wrong and I have to start all over again.

Do you ever think about how a book might be received whilst you’re writing it?

The answer to whether I ever think about how a book might be received whilst I’m writing is no, and yes. My first reader is always myself. I have to receive my work well. It is soul-destroying when I have an inner template of what I want to achieve on the page but the process doesn’t co-operate and I end up putting down something quite awful. This happens more often than I like to admit to, so it is quite a triumph for me when I like what I have written. In that sense I don’t agonise about how other people will receive it. Once the book is on its way to publication, I do hope that people will see in it what I did my best to inscribe into the pages.

There was a gap of 18 years before The Book of Not was published. Were you writing any prose during that time?

For 11 of the 18 years between Nervous Conditions being published and the Book of Not appearing, I lived in Germany, first of all attending film school and later, on starting my family. I’d had to learn enough German to manage at film school, so I didn’t have as close a relationship with the English language as I needed to write. Adjusting from prose to filmcraft was also essentially like learning another language. I started having children while I was at film school and that meant I had to put a lot of creative work on hold. I’d take my daughter to lectures when I didn’t have a baby-sitter. With all that to juggle, I did not have time or head space to engage with the issues I needed to engage with for a sequel to Nervous Conditions, as that book ended with Tambudzai starting secondary school.

Place seems to be a central theme of your work. How has your relationship to Zimbabwe changed over the years and are you positive for the future?

Place has been a central theme in my work so far. I consciously painted pictures of some of the physical elements of Zimbabwe as I’ve known them, as well as of some of the social elements. This was important to me as both landscape and society are changing fast. My aim was to leave a sense of what it was like. My relationship with Zimbabwe has changed tremendously over the years. When I began writing Nervous Conditions in the early 1980s, just after Zimbabwe became independent, I was full of hope for a new, prosperous nation in which Zimbabweans could renew themselves, thrive, contribute to the nation’s growth and to the global community. Those hopes have come to very little. Zimbabweans now have to work out how to create and build a prosperous nation in which citizens can thrive. That is a mammoth task after decades of mis-governance, in an era of neocolonialism when international institutions support the repressive government in various ways because these institutions are in dialogue with the repressive government and not the ordinary repressed people. This global system has the effect of continuing the relations that disadvantage black innovation and excellence, just as the government itself does.

Your novels explore the struggles of female identity in particular. Do you see yourself in dialogue with wider contemporary feminist discourse?

I was definitely in dialogue with wider contemporary feminist discourse when I wrote Nervous Conditions. In that novel, part of my project was to show how feminism accounted for many of the struggles that women in Zimbabwe face on a day-to-day basis throughout their lives. I am now increasingly aware of the intersection of gender with other factors such as race, age, nationality (amongst African nations as well as beyond), and political party membership, which combine to define different life trajectories for different groups of women. With this awareness, my writing has become more nuanced and I strive to engage with intersectionality.

Do you think writers have a responsibility to make work that’s socially engaged on some level?

I think writers have the responsibility to write what they want to write well. As writers are human, their writing is a reflection of human experience. The more we learn of the range of human experiences, the richer we become in our own humanity. Hopefully, we also become better educated to make more sustainable choices.

You also make films and write scripts. Which came first? And are the processes distinct for you or part of a larger, overarching creative aim?

I’ve always been interested in motion pictures. I sat and watched TV for hours on end as a child in my foster home in Dover in the 1960s. That’s how I learnt that television can transport you to other worlds and give you a window into something you’d never experience otherwise, and all in the comfort of your own home. My dad used to take my brother and I to movies too when we went to London to visit our parents. Then, I went back to pre-independence Zimbabwe, where there was no TV at all. There were occasional films, but they never had people in them who looked like me or who moved through worlds like mine. Nor could I understand why all those people kept on shooting each other, so I gravitated toward books, which my dad bought in bulk whenever he could. TV arrived several years after we’d been back, screening those 1970s African American sitcoms which always left me feeling slightly desperate. When Nervous Conditions was published, I found I needed additional income streams to make a living, so I went to film school. The processes are distinct for me. I approach literature as exploration and film as craft. They overlap with adaptation, which for me goes only one way – from book to screen.

I hear you’re currently working on a YA novel. Can you give us any clues as to what to expect?

I’m writing a YA speculative fiction called Sai-Sai and the Great Ancestor of Fire. In it Sai-Sai and two of her school friends are called on by three other Great Ancestors to save their world by defeating the Great Ancestor of Fire. I’m hugely excited to be doing something different and to be inhabiting a different world, but can’t say more at the moment.

Quick-fire Questions

Last book you read?

Bring out the Bodies by Hilary Mantel.

The writer you most admire?

Toni Morrison, for centering her particular world unapologetically while succeeding in making it completely accessible.

Where do you go/what do you if you’re stuck for inspiration?

I read fiction and nonfiction, or go to the gym, when it’s open, or I take a singing lesson. Or pray.

Ideal writing set up?

Eastward looking room, with a large window, facing a garden. This is how I started writing in the 1980s in my mother’s dining room.

A Zimbabwean writer that everyone should read?

Novuyo Tshuma, especially her novel House of Stone.

Any Questions or Tips to add?