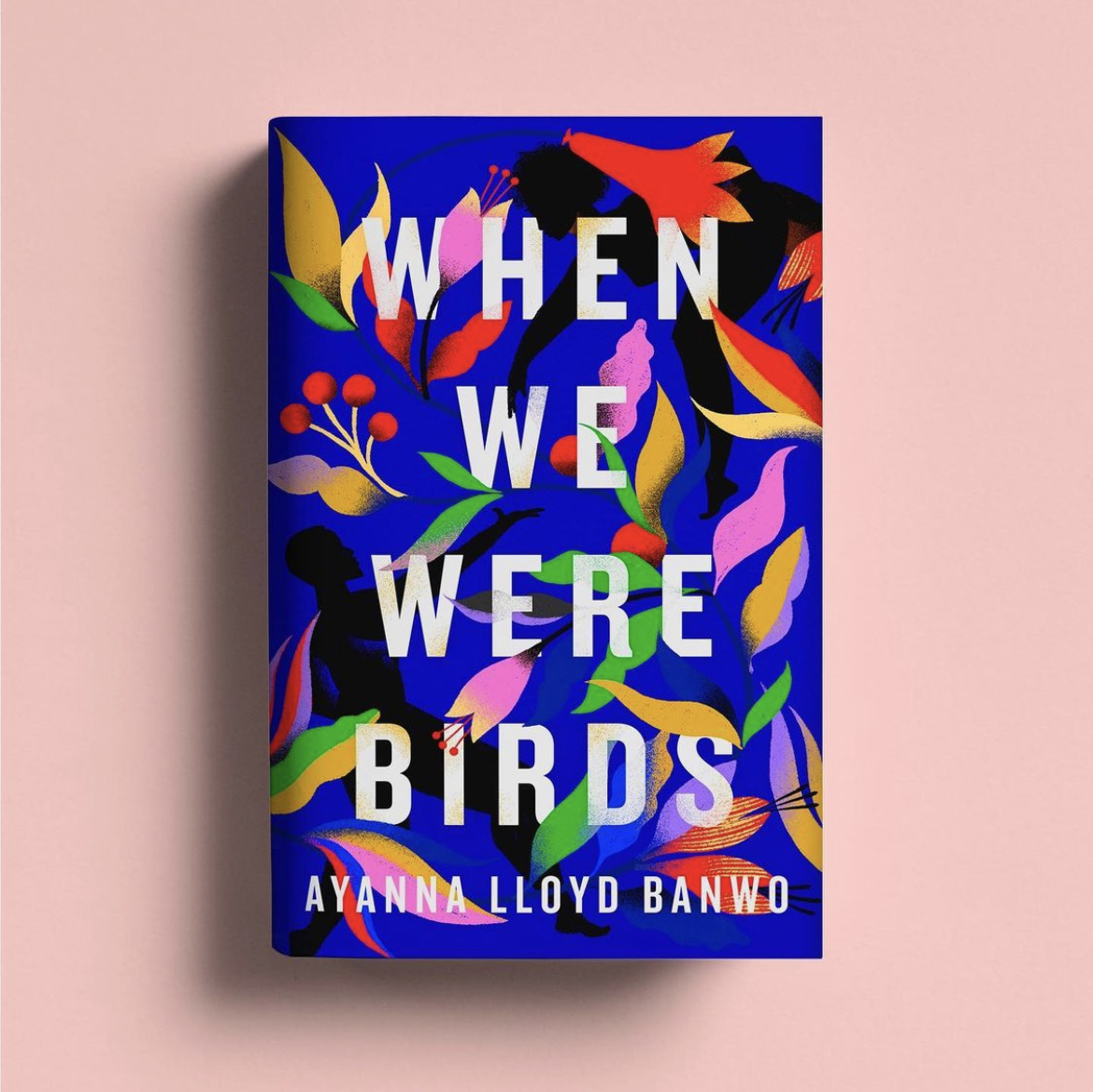

As part of our ongoing series of interviews with contemporary female writers, Millie Walton speaks to Ayanna Lloyd Banwo about her debut novel, writing processes, and connection to place.

Was writing something you always wanted to do?

I think I have to make a distinction between writing, and being a writer. I didn’t know how you went about being a writer, but I always liked stories and I was always reading. My grandmother was a big storyteller, but she was also a big reader. She would buy me and my cousins books so we read a lot and she would tell us stories about Trinidad and growing up. Some things she’d make up just to entertain us, and some of it was about her life and her mum’s life. There was a strong sense of lineage and family history. We knew a lot about family members who died because she talked about them all the time, as though they were there with us, like we would meet them one day. So, stories were always there, but being a writer wasn’t something I considered until my thirties. I was writing before then, but it was just something I did. I didn’t know how to get a story published. You grow up in very modest middle class circumstances, and it’s like, ‘You’re gonna be a writer. What are you gonna do with that?’ The idea is you have a job and I didn’t think writing was a thing that I could do as a job.

What changed that?

Bocas Lit Fest. The festival started in 2011 in Trinidad but I didn’t hear about it until 2012 when I took the time off work to go. It was the first time I met writers. There were always people who were writing stories and self-publishing, but they didn’t look like what I thought a book was supposed to be and doing that felt like a waste of time for me. At the festival, though, there were writers who I’d read and then ran workshops that you could bring your little pile of stories to, and say, ‘Hi! Is this any good and how do I make this better?’ That’s when I realised that there were literary journals and magazines that you could submit to. Other people knew about these opportunities, of course, but I only realised later.

When did you start thinking of yourself as a writer?

Well, I was a lot of things: I was a teacher, I worked in advertising, I worked in corporate communications, I worked in a construction company. I was always working with words but I didn’t think of myself as a writer until around 2013 or 2014. I remember sort of saying to myself, ‘Okay so I have a job that pays the bills and everything else is writing.’ Any time I had a vacation from work, I applied to workshops and residencies. Even though I still didn’t say I was a writer, I started to make writing the focus. The job was because I needed the money, it wasn’t a career path like my friends had.

Credit: Stuart Simpson/Penguin Random House

When did your idea for your novel When We Were Birds start brewing?

I had been trying to write about my mother and death and grief for a while but I couldn’t figure out how to do it. I think the way I was trying to write it was probably too close. It all sort of happened at once: I went to the literary festival in 2012, then my mum died in 2013, my dad the next year, and my grandmother the year after that. I didn’t really have a story but I had the idea of writing about grief and that felt like such a big thing. Because of experiences, I spent a lot of time in cemeteries, in the hospital, in the morgue, and I learnt a lot about the bureaucracy of what it means when somebody dies: standing in line to get death registration and your funeral grant.

Even before then, I had spent quite a bit of time in graveyards. No one from my family had died for a long time and nobody remembered where the graves were because they didn’t have headstones and I used to wonder if walking there, I would somehow know where they were. Then, of course, we had to actually figure out where these plots were. I think it was around then that I really started to think about who the people are that do death work, who cared for us. The most caring thing those people can do for you is to be professional and process your shit quickly. It doesn’t make sense for them to say, ‘I’m sorry for your loss.’ What you want is for them to be as quick and efficient as possible because you need something to go right. You just need them to do their job and to do it properly so you can get out of there and go onto the next thing on your list.

That’s really where the shape of this story came from, and it began with Darwin, with the idea of a character who ends up in this unlikely place, but whose personality actually makes him very suited to death work and to caring for people who are grieving.

Did the idea change at all during the writing process?

This is really where [my experience of studying] at UEA (University of East Anglia) comes in. I went to UEA with this idea of writing a big grief novel and I remember in our first big meeting altogether, one of our tutors said, ‘A lot of you are going to come here thinking that you know what you’re going to write. For the first workshop, bring something that you’re not sure about.’ I had this very rough short story about Darwin, but he was older, more certain, and had made all of these bad decisions. I took that story to the workshop and my tutor said, ‘I think this is what you need to be working on this year.’ That was quite a big thing for me because this book might not have been written at all otherwise. I might have kept on going with the novel that I thought I was going to write, but wasn’t quite ready to write, to be honest.

How do you think your time of studying impacted your thinking about writing more generally?

That first workshop was very affirming for me. As I said, I had been doing lots of workshops in Trinidad, but UEA was the first time that I was around people who were, more or less, only writing. At home, most of my workshops were full of women. Men are arrogant in ways that women aren’t: if they want to write, they shut themselves away and they do their thing, but women look for classes because we’re unsure, we need the affirmation and the women in my classes were generally stealing time to write. They had children, or they were caring for elderly parents, or they had jobs. One week someone would be late because their partner didn’t pick up their kids, or they couldn’t come because a child was sick, but at UEA, everyone had purchased or carved out the year to do this thing that they desperately wanted to do. It felt so indulgent, so beautifully indulgent. I don’t know what other creative writing programs are like, but it also helped that Norwich itself is a writing city. If you walked into a pub with your laptop and took it out, nobody bats an eyelash, they all assume you’re at UEA. Also, in my workshops at home everyone was writing fiction but at UEA, there were people who were writing non-fiction, poetry, plays. Even though we weren’t in the same workshops, we still had social discussions and it always went back to writing because that was our jam, it was what we most wanted to do and what we were all interested in.

The book is set in Trinidad, but it was written, for the larger part, in the UK. How did you transport yourself back there?

It was mainly through memories, but it’s not as though you just sit there and remember everything automatically, you have to mine your memories, you have to unpack them until you get to what something smells, or feels like. Sometimes, memory flattens things, especially when it’s a place you know so well.

Some things I researched, but that was for finer points about how cemeteries work, and the actual mechanism for digging a grave. I’d seen it done before but when you go to a funeral, they’ve already done quite a bit of it so you only see the tail end. What I had to look up is: how is the measuring actually taking place? How do they know how deep to dig? Is it instinctive? I found the methods vary quite a bit. The cemetery in the book is based on a cemetery called Lapeyrouse in Port of Spain which is very old. Everything is very close together. Some cemeteries are very well spaced and they can do the digging mechanically, but in that cemetery everything is dug by hand so it is quite a different process. I also drew on conversations I’d had with grave diggers back home. I’d ask them all these questions and I guess because nobody normally asks them, they answered.

It’s funny where you end up as a writer.

Let me tell you, I’ve been to some dark places on the internet. There are videos of people who actually rob graves: contemporary grave robbers. There was this one I remember of a guy holding a skull. I thought the questions I was asking were creepy but trust me, there’s much worse on forums and they can’t all be writers. The other thing, though, that was really useful was reading about the resurrection men in the US at the beginnings of modern surgery. There were no cadavers for these burgeoning medical schools – I think partly because of the influence of the church and this belief that you couldn’t dig up and operate on good Christians who were buried and their bodies consecrated so, they were limited to criminals and to the cadavers of Africans who were formerly enslaved and buried. The resurrection men were people who literally dug up and robbed graves of their bodies and sold them to these medical schools. It’s interesting how a graveyard can be a peaceful, silent place but there’s also a lot of history of all these nefarious activities.

When We Were Birds begins almost like a fairy tale and there are lots of magical elements woven into a sense of place. Is this something that you set out to do or did it evolve naturally?

Probably a bit of both. I guess it becomes a conversation about genre too. I can’t say I sat down and thought to myself, ‘I’m going to be a magical realism writer’ but when I look back, so much of what I have written has elements of the fantastical or supernatural. It’s partly because that’s what I like but also because I’m a black woman from the Caribbean with a worldview that is based in indigenous spirituality so I don’t know how to separate the magic from the real. There isn’t a separation for me. It’s not that I haven’t written stories which are very straight realism but it feels natural to me that at some point there is something unexplained in the story.

When you say magical realism or fantasy, it prepares you for something that’s going to happen that’s not in the normal vein of reality, but really there’s nothing normal about life. We just spent the last three years living with a plague. People stayed in their houses for six months. There’s nothing ordinary about that. Collectively on the planet, we all lost elders at the same time, the people who were most vulnerable and the repositories of our histories. There were so many babies who were born in that period who aren’t going to know their grandparents. We’re going to feel the psychic toll that that has taken on us for a while.

I think the more we mine reality, the more we come up against the strange and the fantastical. It’s just about how far you want to dig.

Credit: Stuart Simpson/Penguin Random House

That’s interesting because growing up here, in England, you encounter magic as a child but then it’s sort of ironed out of you as an adult and you lose the ability to access that perspective on life.

I think this is why white people are in crisis. You’ve burned all your witches. You’ve got rid of all your fairies. You’ve replaced culture and myth with this flat thing called whiteness, which doesn’t exist. It’s a social construct that is a result of the enlightenment and capitalism and the empire and so on. I don’t think you got a very good deal in the exchange, to be honest.

One of the things I liked about Norwich is that there are parts of Norfolk where it still feels like there’s something in the land, the forests, in the flat bigness of the sky that people are tuned into but in London, there is no land. There’s real estate. There’s property. There are no homes, it’s property. How the hell is shelter a luxury? You can’t just say, ‘Oh I see a nice piece of land there, let me go and build a house.’ The days of that are long gone. In cities, like London, where people are being priced out, how are they supposed to feel a connection to place? Anyway, we could talk about this forever, and it’s partly in the third book that I have in the back of my head right now.

Going back to your characters – how did Yejide come about?

So, in that short story I mentioned, she was the catalyst who made Darwin think differently. She was a woman who came to bury her mother and he met her and they had this conversation that sort of sparked things in him, but she only appeared twice in that story and I didn’t know her backstory or anything about her family. When I came to think about writing the novel, however, I felt that these two characters were quite compelling and so I had to go back and think about who they actually were. Why would this meeting have been such a big deal for Darwin? What would it have been for her? She was the one that I had to get to know more because I already had a bit of him, but the whole novel process was really about mining these two characters. It’s weird to say what kind of writer I am because I’ve only written one book, but for this one at least, I was more character driven.

Do you have a writing routine?

I’m developing one, by force, because I have to: it’s now my job. When I was still writing the book, though, it felt very manic. I would have a bender for a few days when I was really productive and I would get a lot done, and then I was totally depleted and would feel like I had no idea of what I was doing. Coming towards the end, I would get up early, sit at the desk, and force myself to stay there: to finish the chapter or the sequence. Now, I’m trying to stick to that: wake up, come to the desk, have a word count. It doesn’t always work, of course.

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received?

It’s not really advice, but I remember something that a writer said to us in a workshop in Trinidad. He said, ‘If you are not using your writing to overturn something that you see in society that you think needs changing, then what are you doing it for?’ I’m paraphrasing but I think that’s what art is: recreating a world that is different, or more equitable, or true, or whatever it is you don’t see. I think, for him, there was this idea that if you weren’t doing that, it’s kind of self-indulgent. I don’t know if I always do that with my writing, but I think about it quite a bit. We sometimes end up perpetuating stereotypes but you don’t have to when you’re writing fiction because it’s a book, you can make it up. The other thing he said, in the same discussion, is to not think that you’re doing anything revolutionary. You’re always really writing yourself, it’s always versions of you or your experiences and the further you get from that, the more interesting it gets but that’s where you start out. It might sound like two contradictory statements to say that writing has to do with a big idea but also that you’re just writing about yourself but I think that if you’re writing about yourself then you do end up writing about the change you want to see.

Quick Fire

Who’s a writer you think everyone should read?

Toni Morrison.

What’s your favourite place to write?

In pubs. I can write anywhere, but I like being able to pull off into a little corner of a place and to be kind of invisible, but to also see everything happening around me. It can’t be a very noisy pub, more of a daytime pub where there’s a little bit of a buzz.

How do you define a productive day?

When I was writing this book, my idea of productivity was volume. I had to write a lot. Now, it’s different. I think we’ve all aged a lot in the last few years. I feel more tired and I feel like I have to prioritise rest more than I did before so a productive day is when I’ve had a good sleep, I’ve gone for a walk, and I’ve done some writing.

What’s the last book you loved?

Moon Witch, Spider King by Marlon James. It’s the second book in a trilogy. When the first one came out, the reception was a little bit mixed, but I loved this one. He’s just got to the point in his career where he’s got so few fucks left: when you win the Booker Prize pretty young, you get to geek out and write about African dragons and a woman who lives until she’s 200-years old. I love that. It feels like he was doing exactly what he wanted to do, but without being self-indulgent.

And what’s next on your reading list?

Right now, I’m reading Anthony Joseph’s Frequency of Magic because we’re going to be interviewed together. The basic premise of the book is a man who has been writing a novel for the last 40 years and the characters have got so bored that they’ve just wandered off and are living their lives without him. They sort of escape the confines of the book he’s trying to write.

I’m looking forward to Vagabonds! by Eloghosa Osunde. I got sent the proof a while ago and just haven’t got round to reading it yet, but I think it comes out here, in the UK, soon too.

Any Questions or Tips to add?